Last Thursday and Friday, the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met. During the meeting, they repeatedly touted “best practices” based on vaccination schedules of other developed countries (according to “gold standard science, naturally) as their vision for the US vaccine schedule. Unfortunately, from the reports I’ve read and the video excerpts that I’ve seen, the meeting was even more of a disaster than the two previous meetings that have occurred ever since the longtime antivax activist who is currently US Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired all ACIP committee members and replaced them with a combination of antivax cranks and a couple of members who are not antivax but are sufficiently sympathetic to some antivax positions to have made the cut. Not just that, but the reference to “best practices” is a sham, the reasons why are the main topic of this post. Before I move on, though, I must admit that I appreciate how in a commentary for STAT News Dorit Reiss corrected my characterization of the first ACIP meeting with its new antivax members as a clown car by pointing out something very relevant:

Point taken, and it’s a fair one. I would use a certain term that can be abbreviated CF, but on this blog I do try not to use any profanity worse than a common word for bovine excrement (which is really hard to resist at times, given the pseudoscience and quackery I routinely deal with), except perhaps when quoting certain individuals. In any event, given how late I am to the party and how many other excellent science communicators have covered the nitty-gritty of last week’s ACIP meeting, I’m going to approach the question of what ACIP is doing from a somewhat different perspective that, I hope, will put this ACIP meeting into a broader context in terms of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s plan to chip away at US vaccine infrastructure and ultimately eliminate vaccines, all while referring to “best practices” based on “gold standard science.”

A White House press release and Presidential “Truth” about the childhood vaccine schedule

Because I was in a busy clinic all day Thursday in addition to dealing with a family health issue and also because I was busy interviewing candidates for our surgical residency program all morning Friday, I was thus—fortunately or not, depending on your point of view—spared the temptation to watch the proceedings live online and experience the pain that several of my fellow science communicators experienced. I didn’t have time to watch 16 hours worth of video over the weekend either, and given how much excellent deconstructing of the horrifying antivax bullshit (oops, there’s my use of the one swear word!), I thought I would approach what happened using a frame that I haven’t (yet) seen anyone apply to the ACIP apocalypse, starting with a statement released by the White House not long after ACIP came to its miserable end, Aligning United States Core Childhood Vaccine Recommendations with Best Practices from Peer, Developed Countries:

In January 2025, the United States recommended vaccinating all children for 18 diseases, including COVID-19, making our country a high outlier in the number of vaccinations recommended for all children. Peer, developed countries recommend fewer childhood vaccinations — Denmark recommends vaccinations for just 10 diseases with serious morbidity or mortality risks; Japan recommends vaccinations for 14 diseases; and Germany recommends vaccinations for 15 diseases. Other current United States childhood vaccine recommendations also depart from policies in the majority of developed countries. Study is warranted to ensure that Americans are receiving the best, scientifically-supported medical advice in the world.

I hereby direct the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to review best practices from peer, developed countries for core childhood vaccination recommendations — vaccines recommended for all children — and the scientific evidence that informs those best practices, and, if they determine that those best practices are superior to current domestic recommendations, update the United States core childhood vaccine schedule to align with such scientific evidence and best practices from peer, developed countries while preserving access to vaccines currently available to Americans.

Notice the use of the term “best practices” in the title of the press release and four times in the last paragraph. That is very intentional—and deceptive, as I will discuss. Note that the press release didn’t even use the previously favored term misleadingly used by this administration, “gold standard science,” to justify whatever it wants to do anyway. I also note that, even if you accept the framing of the White House statement, if Germany truly does recommend vaccinating against 15 diseases, is the US at allegedly 18 diseases vaccinated against, really that much of an “outlier”?

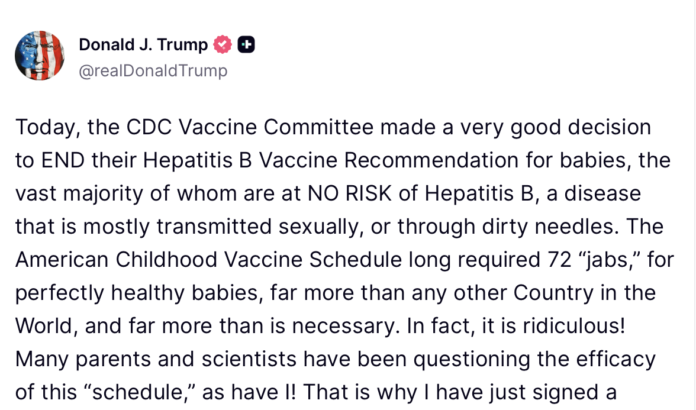

Around the same time, President Donald Trump decided to “Truth” this announcement on his propaganda platform, Truth Social:

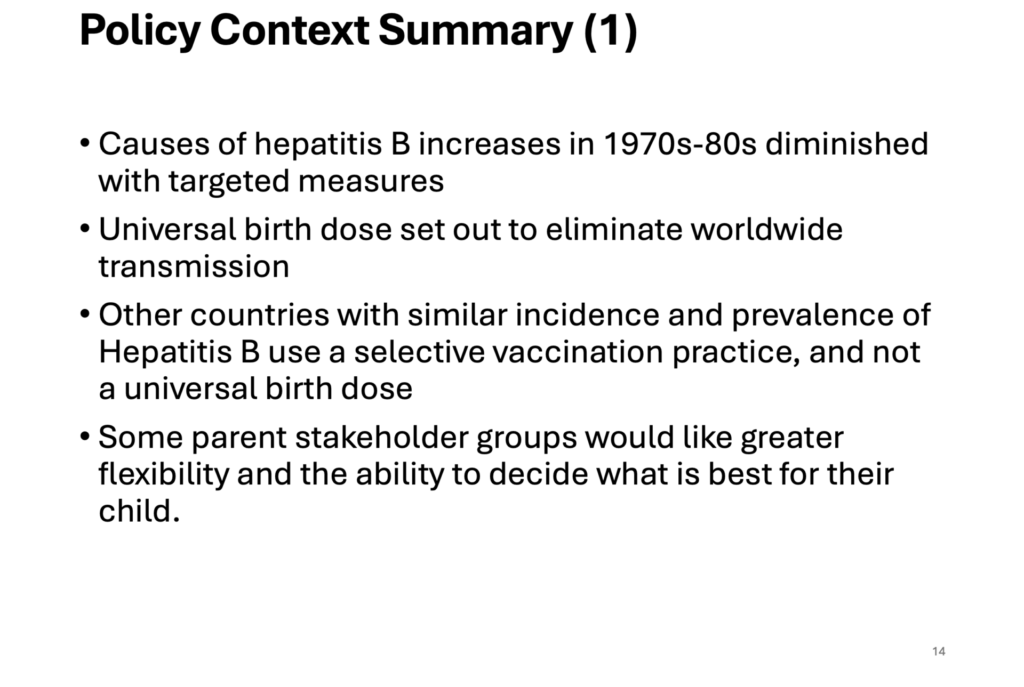

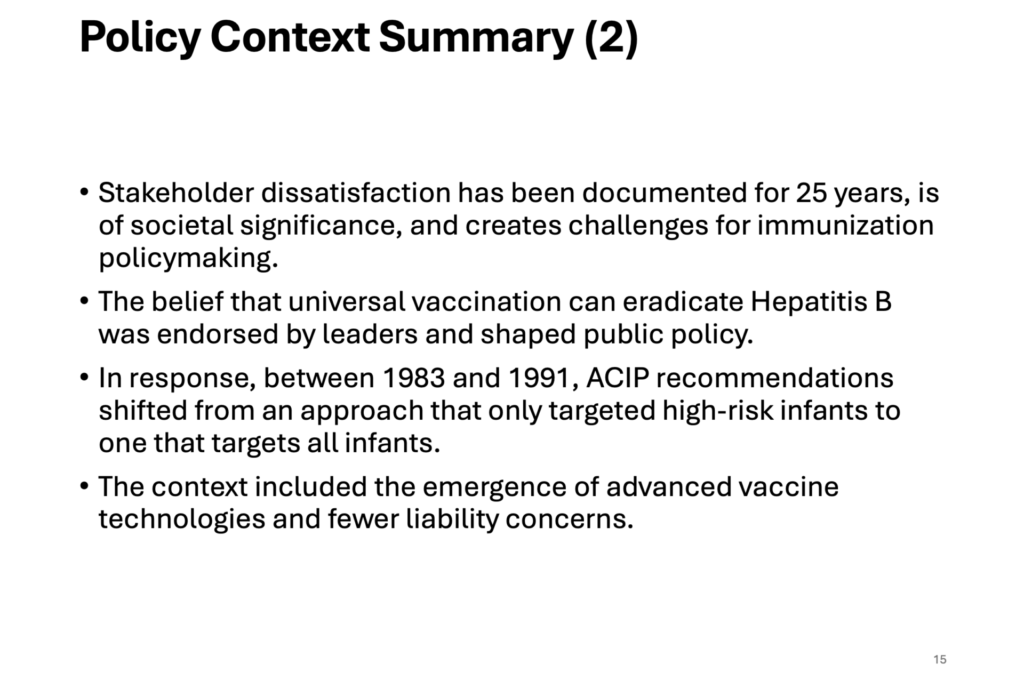

Trump, being Trump, couldn’t even get this quite right. I was convinced before the last ACIP meeting that the newly reconstituted antivax committee would get rid of the birth dose of hepatitis B, but they were (fortunately) too incompetent to do that. The same happened this time around, but, as discussed by Angela Rasmussen, the antivax ACIP did still manage to do some damage:

ACIP voted to recommend delaying the birth dose to up to 2 months in babies born to mothers who test negative for HBV infection, but allowing people to get it if they want it. They also voted to recommend that booster doses be contingent on antibody levels. Together, these will reduce the number of babies who get the HBV vaccine within 24 hours of birth.

She’s right, and she’s also correct when she predicts:

These effects won’t be measurable for years because HBV pathogenesis occurs slowly. Because of the birth dose, HBV prevalence is extremely low in the US. HBV will creep back over time, but it may not be recognized. HBV often doesn’t cause observable clinical disease, so people may not know if they or their babies are infected, especially if they don’t have access to testing. Chronic HBV infection causes liver cancer, but it takes years to develop. The consequences to even a small policy change like this are significant, but it will take decades for their impact to be felt.

I myself have discussed why the original recommendation for a birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine was made and why it makes sense in the US, as have others, including Dr. Vincent Iannelli, going back years. Because hepatitis B is a disease that is transmitted through bodily fluids (e.g., through sexual intercourse and sharing of needles for intravenous drug use), antivaxxers have long been very, very hostile to the birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine, and, unfortunately, it’s been easy for them to misrepresent the science to portray the birth dose as unnecessary at best and harmful at worst. Never mind that there are a number of methods other than vertical transmission through which infants can be infected. So naturally, it was very predictable that the hepatitis B vaccination was always going to be among the first targets of the newly antivax ACIP.

It was also easy for a useful idiot like ACIP member Retsef Levi, an operations manager professor with no strong understanding of immunology, vaccines, infectious disease, or, truth be told, much about medicine, to go on and on about how the risk of hepatitis B in infants is so low, ignoring the obvious inference that the reason the risk of hepatitis B in infants is now so low has been decades of a policy recommending universal vaccination of infants in the neonatal period before they are sent home with their mothers. This was, of course, after a fallacy-filled presentation by Cynthia Nevison, PhD, an antivaxxer whom I called out in 2012 for co-opting the language of skepticism to try to portray vaccine advocates and science communicators refuting the false claim that vaccines were causing an “autism epidemic” as “autism epidemic deniers.” (As the great Charles Pierce would say, only the best people…)

I won’t go over this territory again (much) here, because ACIP’s wishy-washy recommendation is but one of the early volleys in a war on vaccines that will be conducted not just through the weaponization of evidence-based medicine, misrepresentation of what EBM is, and anecdotes of vaccine injuries and death, but through false and deceptive claims that the CDC-recommended childhood vaccine schedule is somehow excessive and not “evidence-based” because other countries have opted for different recommended schedules. I first wrote about this phenomenon way back in 2016 in the context of discussing a point-counterpoint exchange published in the The BMJ as “Head to Head” under the title Is the timing of recommended childhood vaccines evidence based?

Let’s take a look at that article, and I will also add other thoughts that I’ve had in the nearly—unbelievably!— ten years since I last addressed the topic.

“Best practices” and “gold standard science” vs. recommended vaccine schedules

The answer to the question of whether the childhood vaccination schedule is evidence-based depends, of course, on what one means by using the term “evidence-based.” As I concluded in 2016, childhood vaccination schedules are indeed evidence-based, albeit imperfectly so, and that recommended vaccination schedules differ from country to country does not imply that recommended schedules are not evidence-based. The CliffsNotes explanation of the reason why is that the evidence that needs to be considered in each country goes far beyond just randomized clinical trials and vaccine safety monitoring. The evidence considered must take into account different factors, including disease burden from various infectious diseases, demographics, economics, its own unique healthcare system, and other factors. There is no “one-size-fits-all” super-science-based vaccination schedule that will be the same for every country—and never will be. Portraying the CDC-recommended vaccine schedule as some sort of outlier, however, serves the purpose of sowing fear, uncertainty, and doubt about the schedule as a prelude to dismantling it.

The other assumption behind this strategy is the antivax assumption that vaccinating against more diseases is inherently somehow a bad thing. Indeed, it is not uncommon to see charts like this posted pointing out how the US went from vaccinating against eight diseases in the 1970s to 17 diseases now, as though that were a bad thing:

Before I move on, I should point out that the statement that we’re giving 72 doses of vaccines (or even more than 100, as RFK Jr.’s antivax org Children’s Health Defense has claimed at least once, or 200, as antivaxxer Jane Ruby has claimed) is an intentionally deceptive one. Every combination vaccination, for instance, is counted as the number of vaccinations in the combination; e.g., MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) and DTaP (diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis) are counted as three each. As usual, Dr. Vincent Iannelli discussed the deceptiveness of this tactic in detail a few months ago; so, again, I won’t dwell on it more other than to repeat Dr. Iannelli’s estimate that children can get as few as 27 shots over their childhood and be protected. You can read his post if you’re interested in the nitty-gritty. (Naturally, antivaxxers think 27 shots is too many.) The point, to reiterate, is that the assumption behind the “best practices” argument is that countries that recommend fewer vaccines have a more “evidence-based” vaccine schedule than countries that recommend more vaccines. Once you understand that, the tactic becomes very clear: Race to the bottom by citing countries that include the fewest number of vaccines as “best practices” as being somehow more “evidence-based.”

Let’s look, however, at what “evidence-based” means in terms of developing vaccination schedules for a country. For this purpose, I really do like to cite the “yes” response in The BMJ debate from 2016, because it’s a very succinct and understandable response:

Data from clinical trials represent only a portion of the evidence considered in determining vaccination schedules.5 Burden of disease, immunogenicity, and efficacy studies enable countries to select vaccines and schedules appropriate for their populations, as shown by the recent infographic in The BMJ.6 Vaccine schedules are further refined by considerations such as timing and efficiency of access to the target population to optimise uptake. For childhood vaccines, integration with existing local or national well child visit schedules is a critical consideration. This concept was summarised well in the US Institute of Medicine (IoM) report on the childhood immunisation schedule: “Each new vaccine is approved on the basis of a detailed evaluation of both the vaccine itself and the immunization schedule.” The IoM further stated that randomised controlled trials in which children “would receive less than the full immunization schedule or no vaccines would not be ethical because they would be exposed to a greater risk for the development of diseases and community immunity would be compromised.”5

Once vaccines are in general use local surveillance is generally conducted to evaluate their effect on disease burden. Comprehensive surveillance systems are also maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, Eurosurveillance in Europe, and the World Health Organization expanded programme on immunisation (EPI).7 8 9

The article includes a useful infographic that allowed easy comparison of the vaccination schedules of a number of developed countries including the US, Canada, France, the United Kingdom, Russia, Germany, Italy, and Japan. True, the infographic is ten years old and thus does not include COVID-19 vaccines or any changes in national immunization schedules since then, but, even so, I find it rather interesting to note that in 2015 the US was not the country with the most doses of vaccines on its schedule. Germany was, and Canada had nearly as many cumulative doses on its schedule as the US. If you want to compare current vaccination schedules between different countries, Cambridge University maintains a useful website providing links to Global Vaccination Schedules, where it is noted that schedules differ from country to country based on:

- the number of different types of vaccines included

- the manufacturers who supply the vaccines, which leads to different brand names

- the ages at which vaccines and boosters are recommended

- the number of vaccine doses recommended for each vaccine

- the types of vaccines recommended for the whole population

- the types of vaccines recommended for particular groups, such as pregnant people

And that the reasons for this include:

- differences in the epidemiology (patterns and frequency) of the disease in each country

- differences in the way that countries make decisions about which vaccines to offer to everyone

- capacity of the health system to add new vaccines

- cost

- history and tradition (“we have always done it this way”)

Or, as the Infectious Diseases Society of America put it:

that don’t recommend a birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine have universal

healthcare and screening of the pregnant for hepatitis B.

No doubt antivaxxers touting how “evidence-based” they are and that the US vaccination schedule is somehow not “best practice” will pounce on the bullet point on the Cambridge University website about “tradition,” but it’s unclear how much that reason matters in the US, for the simple reason that, for a long time the CDC has had a very strict evidence-based grading system for vaccine recommendations. (More on that later.) The point, however, is:

Due to these differences, there is no single correct immunisation schedule for worldwide use and it is important that you follow the recommended schedule for your region.

This simple observation, of course, is contrary to how this administration is trying to claim that “gold standard science” will lead to discovering “best practices” and that, if the US is an outlier when it comes to any immunization recommendations, it must mean that we are far from following “best practices” with respect to vaccination. Not that that stopped antivax nurse and former board member of RFK Jr.’s antivax org CHD, Vicki Pebsworth from justifying reexamining the US use of the birth dose of hepatitis B vaccination by…vibes:

Where’s the strong evidence base? Pebsworth seems to be arguing that, because “stakeholders” are unhappy with the current recommendation (an “unhappiness” and resistance that her organization and other antivaxxers spent decades stoking), ACIP should reconsider the current recommendation for a birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine.

Meanwhile, Nevison, toeing the Trump administration line, blamed immigrants for the infant hepatitis B cases that the US still sees:

Because of course she did.

What I don’t see here is anything resembling the “gold standard science” that ACIP used to use through its aforementioned Indeed, the whole process is supposed to use what is called an Evidence to Recommendations (EtR) framework that looks at multiple domains. Take a look at the link I just listed, which used to lead you to a CDC document with the framework and the domains to be considered, but now leads to a page that reads “The page you’re looking for was not found.” (It’s very telling that RFK Jr. nuked that webpage, isn’t it?) If you go to the page as archived in the almighty Wayback Machine at Archive.org, you’ll find that, before RFK Jr., CDC recommendations for evaluating evidence included:

- Is the problem of public health importance?

- How substantial are the desired anticipated effects?

- How substantial are the undesired anticipated effects?

- Do the desirable effects outweigh the undesirable effects?

- What is the overall certainty of evidence for the critical outcomes?

- Does the target population feel that the desirable effects are large relative to undesirable effects?

- Is there important uncertainty about or variability in how much people value the main outcomes?

- Is the intervention acceptable to key stakeholders?

- Is the intervention a reasonable and efficient allocation of resources?

- What would be the impact on health equity?

- Is the intervention feasible to implement?

At each stage, to consider each question, evidence is supposed to be evaluated according to the GRADE framework, which systematically rates the quality of evidence available to apply to each question above. In other words, yes, stakeholder opinion was important, but it was just part of the whole framework that emphasized evidence, size of the effects, whether evidence suggested that desirable effects outweigh undesirable effects, and the like, but all of the questions above were previously evaluated according to the GRADE framework, rather than antivax vibes and blaming immigrants, before ACIP could even consider new recommendations.

So why are vaccine schedules so different? It helps to go back to that BMJ “debate.” When it comes to answering the question of how evidence-based vaccine schedules are, there’s only one answer: It’s complicated. It’s complicated as hell. That’s why expert advisory bodies are required to synthesize all the lines of evidence and come up with a reasonable set of recommendations that will, based on what is known at the time, maximize benefit and minimize potential harm, as Edwards et al. also pointed out in 2016, with examples:

In nearly every jurisdiction, decisions regarding vaccine schedules are made by formal advisory bodies consisting of experienced practitioners, public health officials, vaccinologists, and epidemiologists. Available data are reviewed, burden of disease assessed, and practical considerations for vaccine delivery evaluated to produce an appropriate schedule for each country. Thus, expert advisory bodies may develop differing recommended schedules, based on local, regional, or national considerations. For example, the second dose of MMR vaccine is routinely given in Germany at 15-23 months of age, while in the US it is administered at 4 to 6 years. Strong trial-generated evidence shows that two doses separated by at least 28 days and the first dose administered on or after the first birthday will produce measles immunity in 99% or more of people. The timing of the second dose varies in each country based on the ability to provide the earliest possible second dose that will minimise the burden of measles. Ongoing surveillance of measles cases ensures that the timing of doses remains appropriate to the epidemiology of disease.

Contrasted to, for example, Africa:

Consider also the primary vaccination schedule for infants. The EPI schedule recommends immunisation at 6, 10, and 14 weeks in central Africa based on the early burden of vaccine preventable diseases and the need for efficient vaccine delivery when infants are most accessible. In contrast, the primary schedule in North America and much of Europe is 2, 4, and 6 months; in these populations, the lower risk of acquisition of many infectious diseases and better access to care permit vaccination to be incorporated into established well child visits through the first six months of life.

In other words, it’s important in Africa to get children fully immunized as early as is practical because they are more at risk, which, unsurprisingly, results in a different recommended vaccine schedule because African babies aren’t available for well child visits at 2, 4, and 6 months. These are some of the sorts of local practical considerations that result in differences in vaccine schedules, even though all the public health officials responsible for producing these vaccine schedules are looking at more or less the same scientific evidence. Antivaccine warriors never seem to understand that and try to paint any differences in vaccine schedules between nations as evidence of how “unscientific” the process is. This is, of course, nonsense. It is no more unscientific than science-based medicine. The process of selecting vaccines and deciding upon their best timing is a process that is based in science, but this isn’t a perfect world, which means it can’t be based only in science. Other considerations, as I have discussed, come into play and are inextricably linked to the science. The overall goal is to produce the most scientifically rigorous and defensible vaccine schedule possible given the other constraints that impact the decision-making process.

Moreover, the process of evaluating vaccine schedules is never over. It is never complete. As Edwards et al. noted, monitoring is essential and optimizes protection. They discussed a specific example in the UK to illustrate this point, the Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine, noting that the increase in Hib cases after implementation of an Hib conjugate vaccine schedule at 2, 3, and 5 months was observed. This led health officials to change the schedule that moved the dose at 3 months to 12-13 months, which resulted in a reduction of the burden of HiB disease. They also pointed to the introduction of maternal Tdap vaccination to reduce the rate of pertussis in infants too young to be vaccinated in the US and many European countries, a strategy that appeared to have been effective.

Indeed, as one commenter on X, the hellsite formerly known as Twitter, put it in response to claims by Dr. Robert “inventor of mRNA vaccines” Malone during the ACIP deliberations:

He goes on for several more posts/Tweets to explain further. Given how extensively studied the childhood vaccine schedule has been in the US and all over the world, it makes sense that Edwards et al concluded:

In summary, vaccine schedules are evidence based, safe, and highly effective in reducing the global burden of infectious diseases. Evidence to develop and maintain these schedules involves a multifactorial and robust process carried out worldwide. The real world effectiveness is shown by the millions of children spared annually from the morbidity and mortality of vaccine preventable infections.

Which struck me then and strikes me now as rather hard to argue with.

Moreover, it turns out that the vaccination schedules do not differ as much as the antivax propagandists working for President Trump and HHS Secretary RFK Jr. A recent survey of the recommended vaccine schedules of 32 developed countries found:

This study sought to characterize the landscape of general pediatric vaccine recommendations for 32 United States (US) and European, primarily high-income countries. In this cross-sectional descriptive study, pediatric vaccine schedules from 32 countries were collected from publicly accessible government websites. All recommendations for normal-risk, non-pregnant children up to and including the age of 18 were considered. 83.3% (20/24) of vaccines identified were included within at least one country’s general pediatric vaccine schedule. Of these, 9 (45%) were recommended by all 32 countries. The total number of vaccines on countries’ schedules ranged from 11 to 18. Twelve of 32 (37.5%) countries’ schedules included at least one mandatory vaccination, with mandate frequency ranging from 7.1% to 93.8%. Among vaccines with general recommendations, 16 (84.2%) had a consistent number of doses across at least 50% of countries that included them. For most shots, there was general agreement about the age of the first recommended dose. However, numerical differences were noted for the meningococcal, Hepatitis B, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines.

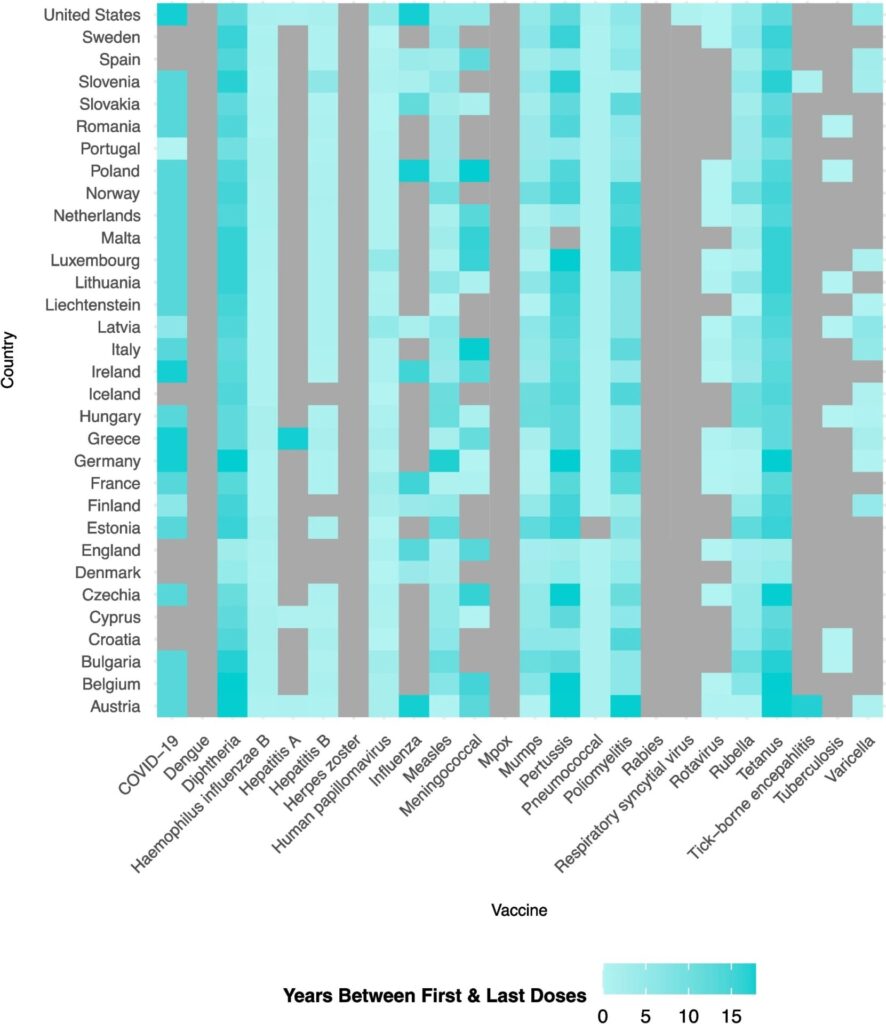

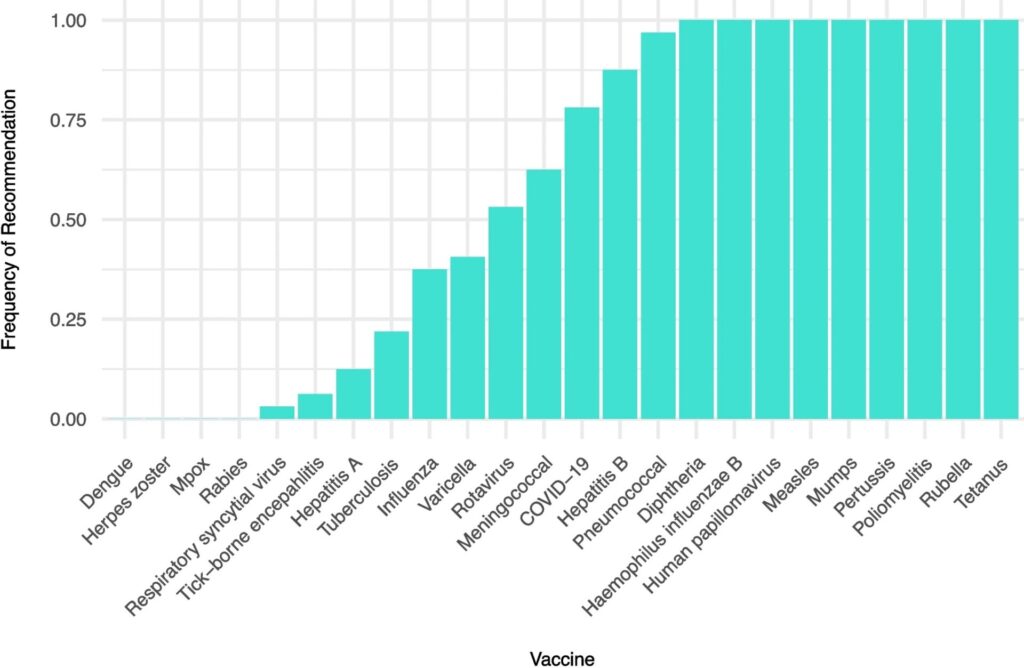

Included are a couple of rather interesting graphs:

And:

Looking at it this way, particularly the last chart, I don’t see as huge a difference as is being portrayed by ACIP. Moreover, I’d challenge the Trump administration on this question: Are you willing to start by assuming that all of the vaccines that are on the recommended schedule for 100% of the countries in this study are safe and effective and therefore should all be on the US schedule? After all, if the US vaccination schedule is going to be based on a popularity contest over which countries include which vaccines in their schedules, at the very minimum, by your own “logic” (such as it is), the US schedule should start with the nine vaccines that all 32 countries recommend.

Of course, aligning the US schedule with that of other high income industrialized countries is not what this narrative is about. It never has been. It’s about casting doubt on the recommended US childhood vaccination schedule and finding excuses to “study” the schedule in order to generate more fear, uncertainty, and doubt to be used as a pretext towards eliminating as many vaccines as possible.

“Best practices” and “gold standard science” at CDC are anything but when it comes to vaccine policy

Ever since COVID-19 hit in early 2020 and COVID-19 vaccines rolled out in December 2020, I’ve repeated a mantra regarding the antivax movement: Everything old is new again. None of what ACIP is doing is new. As I’ve repeatedly emphasized, both here and elsewhere, comparing the US vaccination schedule to those of other countries has been a longstanding antivax trope designed to portray the US as some sort of fanatically zealous overvaccinating “outlier,” with countries that have fewer vaccines on their childhood schedules being portrayed as the height of reason and science (or “best practices,” if you will). This characterization intentionally ignores evidence- and policy-based reasons why vaccination schedules vary between nations. Stepping back to that BMJ debate, it struck me that the arguments supporting the contention that the US vaccination schedule is evidence-based are pretty solid and hard to argue with but, as usual, that didn’t stop Tom Jefferson and Vittorio Demicheli, from trying to argue otherwise nearly a decade ago:

If taken literally, the answer to the question is a simple no. No field trials have compared the effectiveness and harms of all vaccines used according to various schedules listed in the recent BMJ infographic.6 12 The time for such studies is ethically and logistically past.

Ah yes, “too many too soon” and “no one’s done randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of the whole childhood vaccination schedule” rear their ugly head again!

It’s almost as though they know that doing RCTs that leave children unprotected against potentially deadly diseases would be unethical; so they argue by assertion that it is not, without explaining why. As I argued then, even if the question of whether vaccine schedules were evidence-based were taken literally, the answer to the question was still not a “simple no.” The answer to this question can only be a “simple no” if you consider one kind of evidence as trumping all others: RCTs. Note how Jefferson and Demicheli basically bemoaned the fact that no “field trials” have compared the effectiveness and harms of all the vaccines in the various combinations used. It’s clear that when they wrote “field trials” they really meant “RCTs,” because in the very next sentence they pointed out how the time for such trials was ethically past. In fact, we do field trials all the time with respect to vaccines according to the various vaccination schedules. They’re called epidemiology studies, and I could cite a bunch of them then and con cite a bunch of them now. In fact, I’ve discussed a bunch of them over the years. Clearly, Jefferson and Demicheli didn’t consider such trials to be sufficient evidence. That’s why it amused me to see how one of the respondents, Richard J. Roberts, Head of the Vaccine Preventable Disease Programme in Wales called out Jefferson and Demicheli, drily observing:

The opening lines of Jefferson and Demicheli’s argument provide an insight into their view of what constitutes evidence. They state the simple answer to the question ‘Is the timing of recommended childhood vaccines evidence based?’ is ‘no’, because no field trials have been conducted. In doing so they consign all other evidence to the category non-evidence. Such a view is an unaffordable luxury for those who have to make real world decisions on vaccine policy. It also goes some way to explaining why the conclusions of the Cochrane Vaccines Field on vaccine efficacy have on occasion so clearly differed from vaccination policy advised by national expert advisory groups, who are not only free but ethically constrained to consider the totality of the evidence base and not just that provided by trials.

And the beat goes on, because, as I’ve discussed a number of times, EBM methodolatry rules at HHS, not as a strategy to improve the rigor of the scientific evidence backing vaccine policy, but as a strategy for weaponizing the EBM paradigm to cast as much doubt as possible on the safety and efficacy of vaccines, as a prelude for taking them off the CDC-recommended schedule one by one, starting with the birth dose of hepatitis B vaccination under the deceptive banners of “best practices” and “gold standard science.”

After all, EBM maven turned EBM fundamentalist/methodolatrist turned COVID-19 contrarian and antivaxxer, Dr. Vinay Prasad, the man who is now in charge of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) once proposed making the pediatric childhood immunization schedule the subject of a “multi-arm, factorial RCT” in order to “restore trust” in the vaccination schedule. Unfortunately for EBM fundamentalists and methodolatrists, making decisions in the face of incomplete or uncertain evidence is not an uncommon problem faced by public health officials. Sometimes they have the luxury to wait for more evidence. Sometimes they don’t. All the time there will be some level of uncertainty. Within that context, vaccine schedules and timing are indeed evidence-based, if by “evidence” you go beyond just RCT evidence and look at the totality of the science, RCTs, microbiology, immunology, and epidemiology. They are not, however, perfectly evidence-based. They can never be perfectly so. They can, however, be improved, but doing so takes more than just RCTs. It takes looking at the evidence—dare I say it?—holistically. Isn’t that what MAHA claims it’s about?

It’s not, of course. MAHA was never about a holistic look at the totality of the rigorous scientific evidence assessing a question, and the appeal to “best practices” is nothing but a sham, an excuse to start the process of dismantling the US vaccine system by laboring under the delusion that there is one “best” vaccination schedule that is science- and evidence-based. MAHA stans (who are nearly all antivax) will point to variation among nations in their schedules as evidence that we haven’t yet found that One True Schedule yet. Starting from that bogus assumption, appealing “best practices” in vaccination then means pointing to countries that have fewer vaccines on their schedule as being more “evidence-based” and recommending emulating them, whether their schedules are evidence-based for the US or not. The final phase will then involve trying to “prove” that schedules with still fewer vaccines are “superior” to the current “best practices” using a combination of hyped promotion of adverse events that might or might not be due to vaccines and dubious science designed to “prove” that vaccines cause more harm than good.

Before I finish, here’s another thought: What if evidence shows that the US schedule is actually superior to the schedules of our “peer nations” in terms of outcomes? Somehow, I suspect that ACIP would ignore that evidence in favor of continuing to dismantle US childhood vaccination recommendations and infrastructure.

Sadly, there are too many useful idiots or outright collaborators (take your pick depending on the specific person involved, who might be one or the other or both), like Drs. Vinay Prasad, Marty Makary, and the entire membership of ACIP, who are willing to participate in the destruction of evidence-based public health and vaccine policy in the US, all at the bidding of longtime antivaxxer RFK Jr. The physicians in this group are either cranks or have sold their souls for power, and, after they’re done and out of office, we as a nation will pay the price for at least a generation.